Understanding and Implementing Information

Management Concepts and Techniques

JavaScript Front-End Web App Tutorial Part 3: Dealing with Enumerations

Learn how to

build a front-end web application with enumeration attributes, using plain JavaScript

Learn how to

build a front-end web application with enumeration attributes, using plain JavaScript

Warning: This tutorial manuscript may still contain errors and may still be incomplete in certain respects. Please report any issue to Gerd Wagner at [email protected].

This tutorial is also available in the following formats: PDF. You may run the example app from our server, or download it as a ZIP archive file. See also our project page.

Copyright © 2015-2021 Gerd Wagner

This tutorial article, along with any associated source code, is licensed under The Code Project Open License (CPOL), implying that the associated code is provided "as-is", can be modified to create derivative works, can be redistributed, and can be used in commercial applications, but the article must not be distributed or republished without the author's consent.

2021-04-14

Table of Contents

- Foreword

- 1. Enumeration Attributes

- 2. Enumeration Attributes in Plain JS

List of Figures

- 1.1. An example of an extensible enumeration

- 1.2. A single and a multiple

selectelement with no selected option - 1.3. A radio button group

- 1.4. A checkbox group

- 1.5. An information design model for the object type

Book - 2.1. A JS class model for the object type

Book - 2.2. The UI for creating a new book record with enumeration attributes

- 2.3. The object type

Moviedefined together with two enumerations.

List of Tables

This tutorial is Part 3 of our series of six tutorials about model-based development of front-end web applications with plain JavaScript. It shows how to build a web app where model classes have enumeration attributes.

The app supports the four standard data management operations (Create/Read/Update/Delete). The other parts of the tutorial are:

-

Part 1: Building a minimal app.

-

Part 2: Handling constraint validation.

-

Part 4: Managing unidirectional associations, such as the associations between books and publishers, assigning a publisher to a book, and between books and authors, assigning authors to a book.

-

Part 5: Managing bidirectional associations, such as the associations between books and publishers and between books and authors, not only assigning authors and a publisher to a book, but also the other way around, assigning books to authors and to publishers.

-

Part 6: Handling subtype (inheritance) relationships between object types.

You may also want to take a look at our open access book Building Front-End Web Apps with Plain JavaScript, which includes all parts of the tutorial in one document, and complements them with additional material.

Table of Contents

In all application domains, there are string-valued attributes with

a fixed list of possible string values. These attributes are called

enumeration attributes, and the fixed

value lists defining their possible string values are called enumerations. For

instance, when we have to

manage data about people, we often need to include information about their

gender. The possible values of a gender attribute may be

restricted to one of the enumeration

labels "male","female" and

"undetermined", or to one of the enumeration

codes "M", "F" and "U".

Whenever we deal with codes, we also need to have their corresponding

labels, at least in a legend explaining the meaning of each code.

Instead of using the enumeration string values as the internal

values of an enumeration attribute, it is preferable to use a simplified

internal representation for them, such as the positive integers 1, 2, 3,

etc., which enumerate the possible values. However, since these integers

do not reveal their meaning (which is indicated by the enumeration label)

in program code, for readability we rather use special constants, called

enumeration

literals, such as MALE or

M, prefixed by the name of the enumeration like in

this.gender = GenderEL.MALE. Notice that we follow the

convention that the names of enumeration literals are written all upper

case, and that we also use the convention to suffix the name of an

enumeration datatype with "EL" standing for "enumeration literal" (such

that we can recognize from the name GenderEL that each

instance of this datatype is a "gender enumeration literal").

There are also enumerations having records as their instances, such that one of the record fields provides the name of the enumeration literals. An example of such an enumeration is the following list of units of measurement:

Table 1.1. Representing an enumeration of records as a table

| Units of Measurement | ||

|---|---|---|

| Unit Symbol | Unit Name | Dimension |

| m | meter | length |

| kg | kilogram | mass |

| g | gram | mass |

| s | second | time |

| ms | milisecond | time |

Notice that since both the "Unit Symbol" and the "Unit Name" fields are unique, either of them could be used for the name of the enumeration literals.

In summary, we can distinguish between the following three forms of enumerations:

-

simple enumerations define a list of self-explanatory enumeration labels;

-

code lists define a list of code/label pairs.

-

record enumerations consist of a list of records, so they are defined like classes with simple attributes defining the record fields.

These three forms of enumerations are discussed in more detail below.

Notice that, since enumerations are used as the range of enumeration attributes, they are considered to be datatypes.

Enumerations may have further features. For instance, we may want to be able to define a new enumeration by extending an existing enumeration. In programming languages and in other computational languages, enumerations are implemented with different features in different ways. See also the Wikipedia article on enumerations.

A simple enumeration defines a

fixed list of self-explanatory enumeration labels, like in the example

of a GenderEL enumeration shown in the following UML class

diagram:

Since the labels of a simple enumeration are being used, in

capitalized form, as the names of the corresponding enumeration literals

(GenderEL.MALE, GenderEL.FEMALE, etc.), we may

also list the (all upper case) enumeration literals in the UML

enumeration datatype, instead of the corresponding (lower or mixed case)

enumeration labels.

A code list is an enumeration that defines a fixed list of code/label pairs. Unfortunately, the UML concept of an enumeration datatype does not support the distinction between codes as enumeration literals and their labels. For defining both codes and labels in a UML class diagram in the form of an enumeration datatype, we may use the attribute compartment of the data type rectangle and use the codes as attribute names defining the enumeration literals, and set their initial values to the corresponding label. This approach results in a visual representation as in the following diagram:

In the case of a code list, we can use both the codes or the

labels as the names of enumeration literals, but using the codes seems

preferable for brevity (GenderEL.M,

GenderEL.F, etc.). For displaying the value of an

enumeration attribute, it's an option to show not only the label, but

also the code, like "male (M)", provided that there is sufficient space.

If space is an issue, only the code can be shown.

A record enumeration defines a record type with a unique field designated to provide the enumeration literals, and a fixed list of records of that type. In general, a record type is defined by a set of field definitions (in the form of primitive datatype attributes), such that one of the unique fields is defined to be the enumeration literal field, and a set of operation definitions.

Unfortunately, record enumerations, as the most general form of an enumeration datatype, are not supported by the current version of UML (2.5) where the general form of an enumeration is defined as a special kind of datatype (with optional field and operation definitions) having an additional list of unique strings as enumeration literals (shown in a fourth compartment). The UML definition does neither allow designating one of the unique fields as the enumeration literal field, nor does it allow populating an enumeration with records.

Consequently, for showing a record enumeration in a UML class diagram, we need to find a workaround. For instance, if our modeling tool allows adding a drawing, we could draw a rectangle with four compartments, such that the first three of them correspond to the name, properties and operations compartments of a datatype rectangle, and the fourth one is a table with the names of properties/fields defined in the second compartment as column headers, as shown in the following figure.

| UnitEL | ||

|---|---|---|

|

«el» unitSymbol: String unitName: String dimension: String |

||

| Unit Symbol | Unit Name | Dimension |

| m | meter | length |

| kg | kilogram | mass |

| g | gram | mass |

| s | second | time |

| ms | millisecond | time |

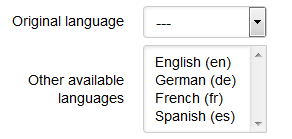

There may be cases of enumerations that need to be extensible, that is, it must be possible to extend their list of enumeration values (labels or code/label pairs) by adding a new one. This can be expressed in a class diagram by appending an ellipsis to the list of enumeration values, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Since enumeration values are internally represented by enumeration literals, which are normally stored as plain positive integers in a database, a new enumeration value can only be added at the end of the value list such that it can be assigned a new index integer without re-assigning the indexes of other enumeration values. Otherwise, the mapping of enumeration indexes to corresponding enumeration values would not be preserved.

Alternatively, if new enumeration values have to be inserted in-between other enumeration values, and their indexes re-assigned, this implies that

-

enumeration indexes are plain sequence numbers and do no longer identify an enumeration value;

-

the value of an enumeration literal can no longer be an enumeration index, but rather has to be an identifying string: preferably the enumeration code in the case of a code list, or the enumeration label, otherwise.

.

An enumeration attribute is an attribute that has an enumeration as its range.

In the user interface, an output field for an enumeration attribute would display the enumeration label, rather than its internal value, the corresponding enumeration index.

For allowing user input to an enumeration attribute, we can use the UI concept of a

(drop-down) selection list, which may be implemented with an

HTML select element, such that the enumeration labels would be used as the text

content of its option elements, while the enumeration indexes would be used as their

values. We have to distinguish between single-valued and

multi-valued enumeration attributes. In the case of a

single-valued enumeration

attribute, we use a standard select element. In the case of a multi-valued enumeration attribute, we use

a

multi-select element with the HTML attribute setting

multiple="multiple".

In the case of using a single-select element for an optional enumeration

attribute, we need to include in its options an element like "---" for indicating that nothing

has been selected. Then, the UI page for the CRUD use case "Create" shows "---" as the initially

selected option.

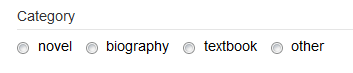

For both cases, an example is shown in Figure 1.2.

While the

single select element for "Original language" shows the

initially selected option "---" denoting "nothing selected", the multiple

select element "Other available languages" shows a small

window displaying four of the options that can be selected.

For usability, the multiple selection list can only be implemented

with an HTML select element, if the number of enumeration

literals does not exceed a certain threshold (like 20), which depends on

the number of options the user can see on the screen without

scrolling.

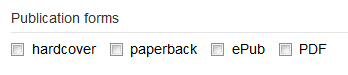

For user input for a single-valued

enumeration attribute, a

radio button

group can be used instead of a single selection

list, if the number of enumeration literals is sufficiently small (say,

not larger than 7). A radio button group is implemented with an HTML

fieldset element acting as a container of labeled

input elements of type "radio", all having the same name,

which is normally equal to the name of the represented enumeration

attribute.

For user input for a multi-valued

enumeration attribute, a

checkbox

group can be used instead of a multiple selection

list, if the number of enumeration literals is sufficiently small (say,

not larger than 7). A checkbox group is implemented with an HTML

fieldset element acting as a container of labeled

input elements of type "checkbox", all having the same name,

which is normally equal to the name of the represented enumeration

attribute.

Defining enumerations is directly supported in information modeling languages (such as in UML Class Diagrams), in data schema languages (such as in XML Schema, but not in SQL), and in many programming languages (such as in C++ and Java, but not in JavaScript).

Unfortunately, standard SQL does not support enumerations. Some DBMS, such as MySQL and Postgres, provide their own extensions of SQL column definitions in the CREATE TABLE statement allowing to define enumeration-valued columns.

A MySQL

enumeration is specified as a list of enumeration labels with the

keyword ENUM within a column definition, like

so:

CREATE TABLE people (

name VARCHAR(40),

gender ENUM('MALE', 'FEMALE', 'UNDETERMINED')

);

A Postgres enumeration is specified as a special user-defined type that can be used in column definitions:

CREATE TYPE GenderEL AS ENUM ('MALE', 'FEMALE', 'UNDETERMINED');

CREATE TABLE people (

name text,

gender GenderEL

)

In XML Schema, an enumeration datatype can be defined as a simple

type restricting the primitive type xs:string in the

following way:

<xs:simpleType name="BookCategoryEL">

<xs:restriction base="xs:string">

<xs:enumeration value="NOVEL"/>

<xs:enumeration value="BIOGRAPHY"/>

<xs:enumeration value="TEXTBOOK"/>

<xs:enumeration value="OTHER"/>

</xs:restriction>

</xs:simpleType>

In JavaScript, we can define an enumeration as a special JS object

having a property for each enumeration literal such that the property's

name is the enumeration literal's name (the enumeration label or code in

upper case) and its value is the corresponding enumeration index. One

approach for implementing this is using the

Object.defineProperties method:

var BookCategoryEL = null;

Object.defineProperties( BookCategoryEL, {

NOVEL: {value: 1, writable: false},

BIOGRAPHY: {value: 2, writable: false},

TEXTBOOK: {value: 3, writable: false},

OTHER: {value: 4, writable: false},

MAX: {value: 4, writable: false},

labels: {value:["novel","biography","textbook","other"],

writable: false}

});

This definition allows using the enumeration literals

BookCategoryEL.NOVEL, BookCategoryEL.BIOGRAPHY

etc., standing for the enumeration indexes 1, 2 , 3 and 4, in program

statements. Notice how this definition takes care of the requirement

that enumeration literals like BookCategoryEL.NOVEL are

constants, the value of which cannot be changed during program

execution. This is achieved with the help of the property descriptor

writable: false in the Object.defineProperties

statement.

We can also use a more generic approach and define a meta-class

Enumeration for creating enumerations in the form of

special JS objects:

function Enumeration( enumLabels) { var i=0, LBL=""; this.MAX = enumLabels.length; this.labels = enumLabels; // generate the enum literals as capitalized keys/properties for (i=1; i <= enumLabels.length; i++) { LBL = enumLabels[i-1].toUpperCase(); this[LBL] = i; } // prevent any runtime change to the enumeration Object.freeze( this); };

Using this Enumeration class allows to define

a new enumeration in the following way:

var BookCategoryEL = new Enumeration(["novel","biography","textbook","other"])

Having an enumeration like BookCategoryEL, we can

then check if an enumeration attribute like category has an

admissible value by testing if its value is not smaller than 1 and not

greater than BookCategoryEL.MAX. Also, the label can be

retrieved in the following way:

formEl.category.value = BookCategoryEL.labels[this.category - 1];

As an example, we consider the following model class

Book with the enumeration attribute

category:

function Book( slots) {

this.isbn = ""; // string

this.title = ""; // string

this.category = 0; // number (BookCategoryEL)

if (arguments.length > 0) {

this.setIsbn( slots.isbn);

this.setTitle( slots.title);

this.setCategory( slots.category);

}

};

For validating input values for the enumeration attribute

category, we can use the following check function:

Book.checkCategory = function (c) { if (!c) { return new MandatoryValueConstraintViolation( "A category must be provided!"); } else if (!Number.isInteger(c) || c < 1 || c > BookCategoryEL.MAX) { return new RangeConstraintViolation( "The category must be a positive integer " + "not greater than "+ BookCategoryEL.MAX +" !"); } else { return new NoConstraintViolation(); } };

Notice how the range constraint defined by the enumeration

BookCategoryEL is checked: it is tested if the input value

c is a positive integer and if it is not greater than

BookCategoryEL.MAX.

We again consider the simple data management problem that we have considered before. So, again, the purpose of our app is to manage information about books. But now we have four additional enumeration attributes, as shown in the UML class diagram in Figure 1.5 below:

-

the single-valued mandatory attribute

originalLanguagewith the enumeration datatypeLanguageELas its range, -

the multi-valued optional attribute

otherAvailableLanguageswith rangeLanguageEL, -

the single-valued mandatory attribute

categorywith rangeBookCategoryEL -

the multi-valued mandatory attribute

publicationFormswith rangePublicationFormEL

Notice that the attributes otherAvailableLanguages and

publicationForms are multivalued, as indicated by their

multiplicity

expressions [*] and [1..*]. This means that the possible values of these

attributes are sets of enumeration literals, such as the set {ePub, PDF},

which can be represented in JavaScript as a corresponding array list of

enumeration literals, [PublicationFormEL.EPUB,

PublicationFormEL.PDF].

The meaning of the design model and its enumeration attributes can be illustrated by a sample data population:

Table 1.2. Sample data for Book

| ISBN | Title | Original language | Other languages | Category | Publication forms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0553345842 | The Mind's I | English (en) | de, es, fr | novel | paperback, ePub, PDF |

| 1463794762 | The Critique of Pure Reason | German (de) | de, es, fr, pt, ru | other | paperback, PDF |

| 1928565379 | The Critique of Practical Reason | German (de) | de, es, fr, pt, ru | other | paperback |

| 0465030793 | I Am A Strange Loop | English (en) | es | textbook | hardcover, ePub |

Table of Contents

In this chapter, we show how to build a front-end web application with enumeration attributes, using plain JavaScript. We also show how to deal with multi-valued attributes because in many cases, enumeration attributes are multi-valued.

Compared to the Validation App discussed in Part 2 (Validation App Tutorial), we now deal with the following new issues:

-

We replace the ES5 constructor-function-based class definition of our model class

Bookwith a corresponding ES6classdefinition, which provides a more convenient syntax while preserving the prototype-based semantics of JS constructor functions. -

Instead of defining explicit setters we now make use of implicit

get/setmethods for properties because they can be conveniently defined within aclassdefinition. -

Enumeration datatypes have to be defined in a suitable way as part of the model code.

-

Enumeration attributes have to be defined in model classes and handled in the user interface with the help of suitable choice widgets.

In terms of coding, the new issues are:

-

In the model code we now have to take care of

-

defining an ES6

classforBook; -

defining

get/setmethods for all properties of theBookclass definition; -

defining the enumerations with the help of a utility class

Enumeration, which is discussed below; -

defining the single-valued enumeration attributes

originalLanguageandcategorytogether with their check functionscheckOriginalLanguageandcheckCategory; -

defining the multi-valued enumeration attributes

otherAvailableLanguagesandpublicationFormstogether with their check functionscheckOtherAvailableLanguagesandcheckPublicationForms; -

extending the methods

Book.updateandBook.prototype.toStringsuch that they take care of the added enumeration attributes; -

defining a

Book.prototype.toJSONfunction for facilitating the conversion from aBookobject to a corresponding JSON record; -

defining extensions of the built-in JS object

Array, representing a class, by adding two class-level functions (maxandmin), and two instance-level functions (cloneandisEqualTo) inbrowserShims.js.

-

-

In the user interface ("view") code we have to take care of

-

adding new table columns in

retrieveAndListAllBooks.htmland suitable choice widgets increateBook.htmlandupateBook.html; -

creating output for the new attributes in

v/retrieveAndListAllBooks.mjs; -

allowing input for the new attributes in

v/createBook.mjsandv/updateBook.mjs.

-

Using the information design model shown in Figure 1.5 above as the starting point, we make a JavaScript class model, essentially by decorating properties with a «get/set» stereotype, implying that they have implicit getters and setters, and by adding (class-level) check methods:

Notice that, for any multi-valued enumeration attribute (like someThings) we

add a class-level check function for single values (like checkSomeThing) and another

one for value sets (like checkSomeThings), both returning an object of type

ConstraintViolation.

The implicit getters and setters implied by the «get/set»

stereotype are a special feature of ES5, allowing to define

methods for getting and setting the value of a property p

while keeping the simple syntax of getting its value with v =

o.p, and setting it with o.p =

expr. They require to define another, internal, property (like _p) for

storing the value of p because the name "p" does not refer to

a normal property, but rather to a pair of get/set methods.

The most common reason for using implicit getters and setters is the need to always check constraints before setting a property. This is also the reason why we use them.

The folder structure of our enumeration app extends the structure of the validation app by

adding the library files browserShims.js and

Enumeration.mjs in the lib folder. Thus, we get

the following folder structure with four files in the lib folder:

publicLibrary

css

lib

browserShims.js

errorTypes.mjs

util.mjs

Enumeration.mjs

src

index.html

In the browserShims.js file, we define a few extensions of the

built-in JS object Array, representing a class, by adding two class-level

functions (max and min), and two instance-level functions

(clone and isEqualTo). These helper functions are used,

e.g., in

v/updateBook.mjs.

In the Enumeration.js file, discussed in the next section, we define

a meta-class Enumeration for creating enumerations as instances of this meta-class

with the help of statements like GenderEL = new Enumeration(["male", "female",

"other"]).

We define an Enumeration meta-class, which supports

both simple enumerations and code lists (but not record enumerations).

While a simple enumeration is defined by a list of labels in the form of a

JS array as the constructor argument such that the labels are used for the

names of the enumeration literals, a code list is defined as a special

kind of key-value map in the form of a JS object as the constructor

argument such that the codes are used for the names of the enumeration

literals. Consequently, the constructor needs to test if the invocation

argument is a JS array or not. The following first part of the code shows

how simple enumerations are created:

function Enumeration( enumArg) { if (Array.isArray( enumArg)) { // a simple enumeration defined by a list of labels if (!enumArg.every( function (l) { return (typeof l === "string"); })) { throw new ConstraintViolation( "A list of enumeration labels must be an array of strings!"); } this.labels = enumArg; this.enumLitNames = this.labels; this.codeList = null; } else if (...) { ... // a code list defined by a code/label map } this.MAX = this.enumLitNames.length; // generate the enumeration literals by capitalizing/normalizing for (let i=1; i <= this.enumLitNames.length; i++) { // replace " " and "-" with "_" const lbl = this.enumLitNames[i-1].replace(/( |-)/g, "_"); // convert to array of words, capitalize them, and re-convert const LBL = lbl.split("_").map( lblPart => lblPart.toUpperCase()).join("_"); // assign enumeration index this[LBL] = i; } Object.freeze( this); };

After setting the MAX property of the newly created

enumeration, the enumeration literals are created in a loop as further

properties of the newly created enumeration such that the property name is

the normalized label string and the value is the index, or sequence

number, starting with 1. Notice that a label string like "text book" or

"text-book" is normalized to the enumeration literal name "TEXT_BOOK",

following a widely used convention for constant names. Finally, by

invoking Object.freeze on the newly created enumeration, all

its properties become 'unwritable' (or read-only).

The following second part of the code shows how code list enumerations are created:

function Enumeration( enumArg) { if (Array.isArray( enumArg)) { // a simple enumeration ... } else if (typeof enumArg === "object" && Object.keys( enumArg).length > 0) { // a code list defined by a code/label map if (!Object.keys( enumArg).every( function (code) { return (typeof enumArg[code] === "string"); })) { throw new OtherConstraintViolation( "All values of a code/label map must be strings!"); } this.codeList = enumArg; // use the codes as the names of enumeration literals this.enumLitNames = Object.keys( this.codeList); this.labels = this.enumLitNames.map( c => `${enumArg[c]} (${c})`); } ... };

Notice that the code list labels in this.labels are

extended by appending their codes in parenthesis.

Three enumerations are coded (within Book.mjs) in the following way

with the help of the meta-class Enumeration:

const PublicationFormEL = new Enumeration(

["hardcover","paperback","ePub","PDF"]);

const BookCategoryEL = new Enumeration(

["novel","biography","textbook","other"]);

const LanguageEL = new Enumeration({"en":"English",

"de":"German", "fr":"French", "es":"Spanish"});

Notice that LanguageEL defines a code list enumeration, while

PublicationFormEL and BookCategoryEL define simple

enumerations.

We want to check if a new property value satisfies all constraints of a property

whenever the value of a property is set. A best practice approach for making sure that new

values are validated before assigned is using a setter method for assigning a property, and

invoking the check in the setter. We can either define an explicit setter method (like

setIsbn) for a property (like isbn), or we can use

JavaScript's

implicit getters and setters in combination with an internal property

name (like _isbn). We

have used explicit setters in the validation app. Now, in the Book class

definition for the enumeration app, we use JavaScript's implicit getters and setters because

they offer a more user-friendly syntax and can be conveniently defined in an ES6 (or ES2015)

class definition.

The properties of the class Book are defined with an internal property name

format (prefixed with _) and assigned with values from corresponding key-value slots of a

slots parameter in the constructor:

class Book {

constructor (slots) {

// assign default values to mandatory properties

this._isbn = ""; // string

this._title = ""; // string

...

// is constructor invoked with a non-empty slots argument?

if (typeof slots === "object" && Object.keys( slots).length > 0) {

// assign properties by invoking implicit setters

this.isbn = slots.isbn;

this.title = slots.title;

...

}

}

...

}

For each property, we define implicit getters and setters using the

predefined JS keywords get and

set:

class Book { ... get isbn() { return this._isbn; } set isbn( n) { var validationResult = Book.checkIsbnAsId( n); if (validationResult instanceof NoConstraintViolation) { this._isbn = n; } else { throw validationResult; } } ... }

Notice that the implicit getters and setters access the corresponding internal property,

like _isbn. This approach is based on the assumption that this internal property

is

normally not accessed directly, but only via its getter or setter. Since we can normally assume

that developers comply with this rule (and that there is no malicious developer in the team),

this approach is normally safe enough. However, there is also a proposal to increase the safety

(for avoiding direct access) by generating random names for the internal properties with the

help of the ES2015 Symbol class.

Code the enumeration attribute checks in the form of class-level

('static') functions that check if the argument is a valid enumeration

index not smaller than 1 and not greater than the enumeration's MAX

value. For instance, for the checkOriginalLanguage function

we obtain the following code:

class Book { ... static checkOriginalLanguage( ol) { if (ol === undefined || ol === "") { return new MandatoryValueConstraintViolation( "An original language must be provided!"); } else if (!isIntegerOrIntegerString( ol) || parseInt(ol) < 1 || parseInt(ol) > LanguageEL.MAX) { return new RangeConstraintViolation( `Invalid value for original language: ${ol}`); } else { return new NoConstraintViolation(); } } ... }

For a multi-valued enumeration attribute, such as

publicationForms, we break down the validation code into

two check functions, one for checking if a value is a valid enumeration

index (checkPublicationForm), and another one for checking

if all members of a set of values are valid enumeration indexes

(checkPublicationForms). The first check is coded as

follows:

static checkPublicationForm( p) {

if (p == undefined) {

return new MandatoryValueConstraintViolation(

"No publication form provided!");

} else if (!Number.isInteger( p) || p < 1 ||

p > PublicationFormEL.MAX) {

return new RangeConstraintViolation(

`Invalid value for publication form: ${p}`);

} else {

return new NoConstraintViolation();

}

}

The second check first tests if the argument is a non-empty array (representing a collection with at least one element) and then checks all elements of the array in a loop:

static checkPublicationForms( pubForms) {

if (!pubForms || (Array.isArray( pubForms) &&

pubForms.length === 0)) {

return new MandatoryValueConstraintViolation(

"No publication form provided!");

} else if (!Array.isArray( pubForms)) {

return new RangeConstraintViolation(

"The value of publicationForms must be an array!");

} else {

for (let i of pubForms.keys()) {

const validationResult = Book.checkPublicationForm( pubForms[i]);

if (!(validationResult instanceof NoConstraintViolation)) {

return validationResult;

}

}

return new NoConstraintViolation();

}

}

The object serialization function toString() now needs to include the values of enumeration

attributes:

class Book { ... toString() { return `Book{ ISBN: ${this.isbn}, title: ${this.title}, originalLanguage: ${this.originalLanguage}, otherAvailableLanguages: ${this.otherAvailableLanguages.toString()}, category: ${this.category}, publicationForms: ${this.publicationForms.toString()} }`; }

Notice that for the multi-valued enumeration attributes we call the

toString() function that is predefined for JS arrays.

There are only two new issues in the data management operations compared to the validation app:

-

We have to make sure that the

cloneObjectmethod, which is used inBook.update, takes care of copying array-valued attributes, which we didn't have before (in the validation app). -

In the

Book.updatemethod we now have to check if the values of array-valued attributes have changed, which requires to test if two arrays are equal or not. For code readability, we add an array equality test method toArray.prototypeinbrowserShims.js, like so:Array.prototype.isEqualTo = function (a2) { return (this.length === a2.length) && this.every( function( el, i) { return el === a2[i]; }); };This allows us to express these tests in the following way:

if (!book.publicationForms.isEqualTo( slots.publicationForms)) { book.publicationForms = slots.publicationForms; updatedProperties.push("publicationForms"); }

In the test data records that are created by Book.createTestData(), we now

have to provide values for single- and multi-valued enumeration attributes. For readability,

we use enumeration literals instead of enumeration

indexes:

Book.generateTestData = function () {

try {

Book.instances["006251587X"] = new Book({isbn:"006251587X",

title:"Weaving the Web", originalLanguage: LanguageEL.EN,

otherAvailableLanguages: [LanguageEL.DE, LanguageEL.FR],

category: BookCategoryEL.NOVEL,

publicationForms: [PublicationFormEL.EPUB,

PublicationFormEL.PDF]

});

...

Book.saveAll();

} catch (e) {

console.log(`${e.constructor.name}: ${e.message}`);

}

};

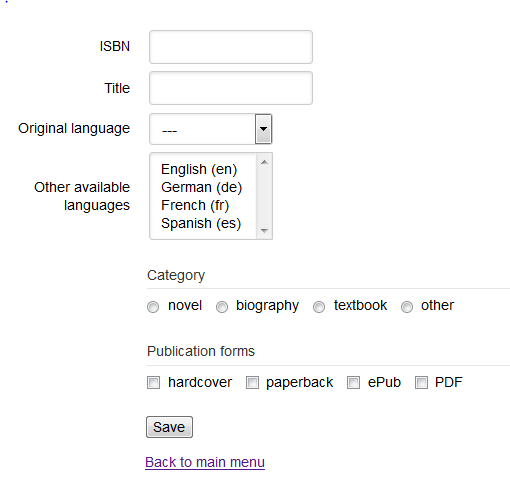

The example app's user interface (UI) for creating a new book record looks as in Figure 2.2 below.

Notice that the UI contains four choice widgets:

-

a single selection list for the attribute

originalLanguage, -

a multiple selection list for the attribute

otherAvailableLanguages, -

a radio button group for the attribute

category, and -

a checkbox group for the attribute

publicationForms.

We use HTML selection lists for rendering the enumeration attributes

originalLanguage and otherAvailableLanguages in the HTML

forms

in createBook.html and upateBook.html. Since the

attribute otherAvailableLanguages is multi-valued, we need a multiple selection list for it,

as shown in the following HTML code:

<form id="Book"> <div><label>ISBN: <input name="isbn" type="text" /></label></div> <div><label>Title: <input name="title" type="text" /></label></div> <div><label>Original language: <select name="originalLanguage"></select> </label></div> <div class="multi-sel"><label>Also available in: <select name="otherAvailableLanguages" multiple="multiple" rows="4"></select> </label></div> ... <div><button type="submit" name="commit">Save </button></div> </form>

While we define the select container elements for these selection lists in

the HTML code of createBook.html and

upateBook.html, we fill in their option child

elements

dynamically in the setupUserInterface methods in

v/createBook.mjs and v/updateBook.mjs with the

help of the utility method fillSelectWithOptions.

In the case of a single select element, the user's

single-valued selection can be retrieved from the value

attribute of the select element, while in the case of a

multiple select element, the user's multi-valued selection

can be retrieved from the selectedOptions attribute of the

select element.

Notice that the div element containing the multiple

selection list for otherAvailableLanguages has the

class value "multi-sel", which is used for defining

specific CSS rules that adjust the element's size.

Since the enumeration attributes category and publicationForms

do not have more than seven possible values, we can use a radio button

group and a checkbox group for rendering them in

an HTML-form-based UI. These choice widgets are formed with the help of the container element

fieldset and its child element legend as shown in the

following HTML

fragment:

<form id="Book"> ... <fieldset data-bind="category"> <legend>Category</legend></fieldset> <fieldset data-bind="publicationForms"> <legend>Publication forms</legend></fieldset> <div><button type="submit" name="commit">Save </button></div> </form>

Notice that we use a custom attribute data-bind for

indicating to which attribute of the underlying model class the choice

widget is bound.

In the same way as the option child elements of a selection list, also the

labeled input child elements of a choice widget are

created

dynamically with the help of the utility method createChoiceWidget in

v/createBook.js and v/updateBook.js.

const formEl = document.forms["Book"],

origLangSelEl = formEl["originalLanguage"],

otherAvailLangSelEl = formEl["otherAvailableLanguages"],

categoryFieldsetEl = formEl.querySelector(

"fieldset[data-bind='category']"),

pubFormsFieldsetEl = formEl.querySelector(

"fieldset[data-bind='publicationForms']"),

saveButton = formEl["commit"];

// load all book records

Book.retrieveAll();

// set up the originalLanguage selection list

fillSelectWithOptions( origLangSelEl, LanguageEL.labels);

// set up the otherAvailableLanguages selection list

fillSelectWithOptions( otherAvailLangSelEl, LanguageEL.labels);

// set up the category radio button group

createChoiceWidget( categoryFieldsetEl, "category", [],

"radio", BookCategoryEL.labels, true);

// set up the publicationForms checkbox group

createChoiceWidget( pubFormsFieldsetEl, "publicationForms", [],

"checkbox", PublicationFormEL.labels);

Notice that like a selection list implemented with the HTML select element

that provides the user's selection in the value or selectedOptions

attribute, our choice widgets also need a DOM attribute that holds the user's single- or

multi-valued choice. We dynamically add a custom attribute data-value to the

choice widget's fieldset element for this purpose in

createChoiceWidget.

Since choice widgets do not allow arbitrary user input, we do not have to check constraints such as range constraints or pattern constraints on user input, but only mandatory value constraints. This allows simplifying responsive validation in the UI.

In our example app, the enumeration attributes

originalLanguage, category and

publicationForms are mandatory, while

otherAvailableLanguages is optional.

In the case of a mandatory

single-valued enumeration attribute like

originalLanguage rendered as a single selection list, we

can enforce a choice, and thus the mandatory value constraint, by not

offering an empty or void option among the option

sub-elements of the select element. If the attribute is

rendered as a radio button group, we can enforce a choice, and thus the

mandatory value constraint, in the create use case by initially setting the

checked attribute of the first radio button to

true and not allowing the user to directly uncheck a

button. In this way, if the user doesn't check any button, the first one

is the default choice.

In the case of an optional

single-valued enumeration attribute rendered as a

single-selection list, we need to include an empty or void option (e.g.,

in the form of a string like "---"). If the attribute is rendered as a

radio button group, we do not check any button initially and we need to

allow the user to directly uncheck a button with a mouse click in a

click event listener.

In the case of a mandatory multi-valued enumeration

attribute like publicationForms rendered as a multiple-selection list or

checkbox group, we need to check if the user has chosen at least one option. Whenever the

user selects or unselects an option in a select element, a change

event is raised by the browser, so we can implement the responsive mandatory value

constraint validation as an event listener for change events on the

select element, by testing if the list of selectedOptions is

empty. If the attribute is rendered as a checkbox group, we need an event listener for

click events added on the fieldset element and testing

if the

widget's value set is non-empty, as shown in the following example code fragment:

pubFormsFieldsetEl.addEventListener("click", function () {

const val = pubFormsFieldsetEl.getAttribute("data-value");

formEl.publicationForms[0].setCustomValidity(

(!val || Array.isArray(val) && val.length === 0) ?

"At least one publication form must be selected!":"" );

});

Notice that the HTML5 constraint validation API does not allow to

indicate a constraint violation on a fieldset element (as

the container element of a choice widget). As a workaround, we use the

first checkbox element of the publicationForms choice

widget, which can be accessed with

formEl.publicationForms[0], for invoking the

setCustomValidity method that indicates a constraint

violation if its argument is a non-empty (message) string.

You can run the enumeration app from our server or download the code as a ZIP archive file.

The purpose of the app to be built is managing information about

movies. The app deals with just one object type, Movie, and

with two enumerations, as depicted in the following class diagram. In the

subsequent parts of the tutorial, you will extend this simple app by

adding actors and directors as further model classes, and the associations

between them.

First make a list of all the constraints that have been expressed in this model. Then code the app by following the guidance of this tutorial and the Validation Tutorial.

Compared to the practice project of our validation tutorial, two

attributes have been added: the optional single-valued enumeration

attribute rating, and the multi-valued enumeration attribute

genres.

Following the tutorial, you have to take care of

-

defining the enumeration data types

MovieRatingELandGenreELwith the help of the meta-classEnumeration; -

defining the single-valued enumeration attribute

Movie::ratingtogether with a check and a setter; -

defining the multi-valued enumeration attributes

Movie::genrestogether with a check and a setter; -

extending the methods

Movie.update, andMovie.prototype.toStringsuch that they take care of the added enumeration attributes.

in the model code of your app, while In the user interface ("view") code you have to take care of

-

adding new table columns in

retrieveAndListAllMovies.htmland suitable form controls (such as selection lists, radio button groups or checkbox groups) increateMovie.htmlandupateMovie.html; -

creating output for the new attributes in

v/retrieveAndListAllMovies.mjs; -

allowing input for the new attributes in

v/createMovie.mjsandv/upateMovie.mjs.

You can use the following sample data for testing your app:

Table 2.1. Sample data

| Movie ID | Title | Rating | Genres |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pulp Fiction | R | Crime, Drama |

| 2 | Star Wars | PG | Action, Adventure, Fantasy, Sci-Fi |

| 3 | Casablanca | PG | Drama, Film-Noir, Romance, War |

| 4 | The Godfather | R | Crime, Drama |

In this assignment, and in all further assignments, you have to make sure that your pages comply with the XML syntax of HTML5 (by means of XHTML5 validation), and that your JavaScript code complies with our Coding Guidelines and is checked with JSHint (http://www.jshint.com).